While researchers agree that activating the graph schema is the most crucial stage in graph comprehension ( Bertin, 1983 Pinker, 1990), it is disputable to what extent different graph types overlap in or share graph schemas. In contrast, pie charts and doughnut graphs belong to an “O-shaped” graph schema characterized by a circular space defined by polar coordinates (angle and distance from center). For instance, bar graphs and line graphs are characterized by an “L-shaped” graph schema with horizontal and vertical axes that define a Cartesian coordinate system. Different cognitive models of graph comprehension (e.g., Pinker, 1990 Lohse, 1993 Padilla et al., 2018) suggest that people have graph schemas stored in long-term memory and that comprehension of a given graph requires that the visually encoded stimulus is matched to the appropriate graph schema ( Kosslyn, 1989). One of the most essential questions is how we decode information from graphs. The utility of line and bar graphs has been wellsupported by a body of experimental research ( Spence, 2006) and the formats have been integrated into the education curriculums used throughout the world to develop children's ability to read and construct data visualizations ( Börner et al., 2019 Franconeri et al., 2021). Line and bar graphs were published by Playfair in 1786 ( Spence, 2006). Reimann et al., 2022) and have been in use since the early days of statistical graphing: The pie chart appears in William Playfair's Statistical Breviary of 1801. While there is a multitude of graph types ( Garcia-Retamero and Cokely, 2017 Padilla et al., 2018 Franconeri et al., 2021), some formats seem to be characterized by high typicality (cf. Experimental evidence has shown that it is easier to understand, communicate and reason about information when it is presented in graphic representations ( Tufte, 1983 Wainer, 1992 Kastellec and Leoni, 2007). ( Zacks et al., 2002 Shah et al., 2005 Ratwani et al., 2008 Garcia-Retamero and Cokely, 2017 Padilla et al., 2018, for reviews Franconeri et al., 2021). Graphs are widely and increasingly employed to visualize quantitative information in science, marketing, sports, politics, etc. We found that bar graphs yielded the fastest group comparisons compared to line graphs and pie graphs, suggesting that they are the most suitable when used to compare discrete groups. Apart from investigating graph schemas, the study provided evidence for performance differences among graph types. Taken together, the pattern of results is consistent with a hierarchical view according to which a graph schema consists of parts shared for different graphs and parts that are specific for each graph type. This implies that results were not in line with completely distinct schemas for different graph types either. Smaller switch costs in Experiment 1 suggested that the graph schemas of bar and line graphs overlap more strongly than those of bar graphs and pie graphs or line graphs and pie graphs. Interestingly, there was tentative evidence for differences in switch costs among different pairings of graph types. As switch costs were observed in all pairings of graph types, none of the different pairs of graph types tested seems to fully share a common schema. The slowing of RTs in switch trials in comparison to trials with only one graph type can indicate to what extent the graph schemas differ.

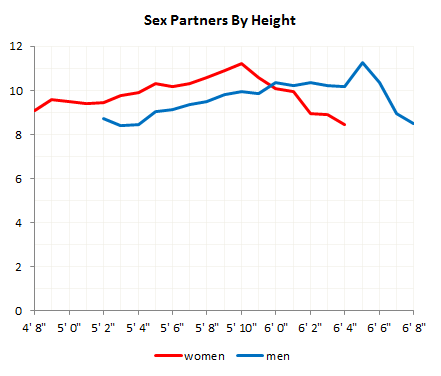

#Graph to compare heights and gender trial

We scrutinized whether switching the type of graph from one trial to the next prolonged RTs. On each trial, participants received a data graph presenting the data from three groups and were to determine the numerical difference of group A and group B displayed in the graph. Two graph types were examined at a time (Experiment 1: bar vs. A switching paradigm was used in three experiments. Furthermore, it was of interest which graph type (bar, line, or pie) is optimal for comparing discrete groups. This study examined whether graph schemas are based on perceptual features (i.e., each graph type, e.g., bar or line graph, has its own graph schema) or common invariant structures (i.e., graph types share common schemas). 2Department of Psychology, FernUniversität in Hagen, Hagen, Germanyĭifferent graph types may differ in their suitability to support group comparisons, due to the underlying graph schemas.1Center of Advanced Technology for Assisted Learning and Predictive Analytics, FernUniversität in Hagen, Hagen, Germany.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)